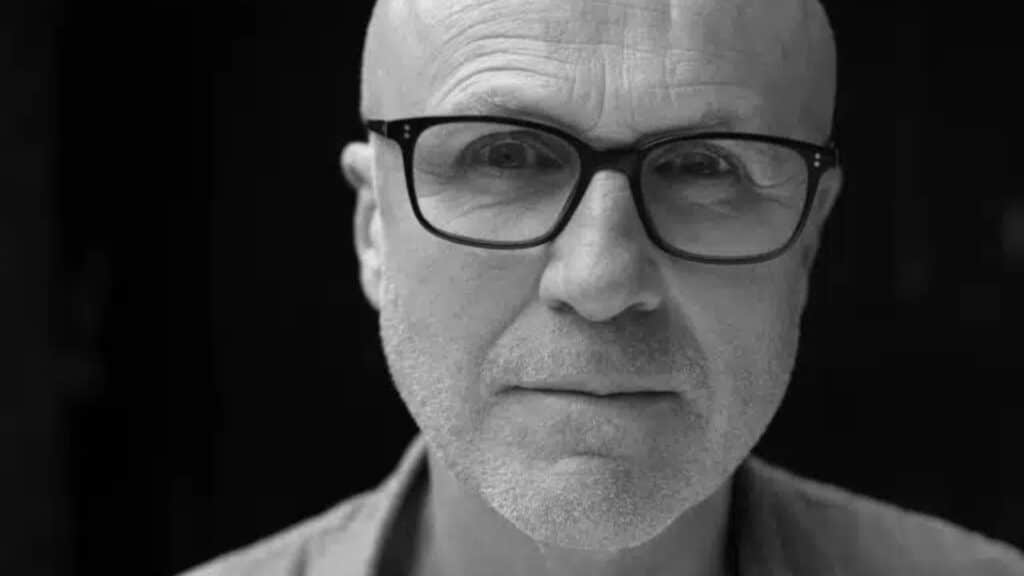

We spoke to playwright Tim Crouch about writing, art, success and more…

- What was the first piece of theatre (or other art!) that made you want to write, or be an artist?

Any artist’s work is the result of countless micro-influences. I can’t pick one or identify the first. I was raised by two English teachers; books and plays were in the house. A drama teacher at secondary school taught me that I could improvise in front of an audience. A theatre collective I was part of in my 20s taught me I could devise and share authorship. I didn’t try to write for myself until I was in my late-thirties.

Ironically, the work I’ve found most inspiring as an audience member is often the work that has left me feeling most stymied as a writer. I am overawed by it. How could I ever emulate that? Why would I want to when it already exists? The work that most fired me up to start writing was the work that I had most problems with. Things that I felt needed a corrective. Something that I could counter.

In my plays there are traces of the history of my theatre going, my reading and my art-watching – from the start. The community focus of the small scale touring companies of the 80s and 90s, the minimalism of Samuel Beckett, the brevity and heart of Raymond Carver, the ideologies and good-nights-out of Bertolt Brecht and John Mcgrath, the conceptual energy of the Young British Artists, the intellectual playfulness of Italo Calvino and Georges Perec, the formal inventiveness of Caryl Churchill, the controlled anarchy of Forced Entertainment. And so on. These things are all in there somewhere.

- How do you define success?

My plays are driven by ideas. I would define success on my terms as being able to push those ideas as far as I can in my writing (without neglecting the need to also have a good time!). Because the ideas steer my work I’m fascinated when people dismiss them. I don’t feel rejected personally. I’m intrigued by bad reviews for my work – they’re the only reviews I read. They’re the ones I post. Maybe if ALL my reviews were bad I would do something about it, but I’m inspired by the thought that we are all different. Some of us voted for Brexit. Some of us think Trump is god’s representative on earth. How could I possibly want to make work that everyone likes?

So I’m okay if it’s not everyone’s cup of tea. Likewise, standing ovations are no signifier of success for me. I’ve written two plays that almost wilfully prevent the audience from clapping at the end – I, Malvolio and The Author. My work is asking us to think. I’m not asking to be loved. I try to keep my ego out of it. The ideas respond to the ideas. If some people are into them then I am happy.

- What or who inspires you?

There’s a work of visual/conceptual art that has had a profound influence on my work. Michael Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree (I wrote a play of that name as a response to it). Made in 1973, this work is simultaneously simple and mind-blowing. It’s a glass of water on a shelf. A glass of water that Craig-Martin claims to have transformed into an oak tree – ‘the oak tree is physically present but in the form of the glass of water’. It presents the sine qua non of all art – the idea of one thing inside something else. This simple act of transformation is at the heart of all children’s imaginative play, and I would say that children are also a major inspiration for me. I make a lot of work for young people. At the heart of my practice, I think, is a sort of prelapsarian devotion to the idea of ‘play’. I see my work as trying to get back to a place in early childhood where the imagination allows anything to be anything. I think that in art anything can be anything – and we have got stuck in the grown-up realism-mud for far too long. I’m inspired, therefore, by anything that offers me a freedom to see the idea of one thing inside something else.

- What does a writing day in the life of Tim Crouch look like?

No pattern. I’m not only a writer – who is? I perform in much of my work and I tour. The touring is how I make a living, so writing gets done in the spaces in between. Also, my performing influences my writing. I learn things on stage that find their way back into the plays I’m working on.

I’ve only recently acquired a designated work room of my own at home. I have a desk but I rarely sit at it. I mostly sit on an old sofa with my lap top correctly designated: on top of my lap. I drink tea. I have Freedom software that switches off the internet for timed periods. I’ve been known to give my phone to my wife to hide from me. It’s calamitous to have the whole world of the internet just beneath that Microsoft Word document you’re meant to be working on.

I write in short bursts. An idea that I think is genius, an hour later becomes embarrassing nonsense. I have to go over and over old ground. Each time I re-engage with a play I usually read from the beginning to where I’ve got to. I need to understand the future of what I’ll write in relation to the past of what I’ve written. I am the worst person to be advising anyone on a writing routine. My wife, Julia Crouch, has the best work ethic. She’s an advocate of the NaNoWriMo model of just writing forward all the time. Of getting a first draft out quickly and then editing and editing. This is a brilliant model. I am not like that. I squeeze a first draft out like the end of the toothpaste – in between emptying the bins and browsing the fridge and fannying around.

- If you feel stuck, do you have a trick for reigniting your inspiration? / What happens if you get writer’s block?

I walk away from it. I do something else. Or rather this is the advice I’d give to anyone in that situation. Very often this adviser doesn’t follow his own advice and I sit staring at my laptop screen for hours on end with nothing happening – which is maybe also a necessary stage of the process. Trust that something is happening even if it doesn’t feel like it. A good thing to do is to switch off your writing brain and switch on your reading brain: pick up a book. Any book. As you read, your stuck brain will loosen and ideas will start to flow again. Switch off your playwriting brain and switch on your audience brain – go see something, a play, an exhibition, a film. You might think you’re not writing – but you are!

Trust that your instinct will get you there in the end. Trust that you’re still writing even when you’re not actually writing. My best ideas have come when I’m least expecting them. Be prepared for it to take a long time. I’m one of the world’s slow playwright. Ideas form glacially and then the connections between them form even slower. Remember that you’re creating a whole new world – with new rules, a new lexicon. Don’t expect things to happen quickly. Good things take their time.

- How much to you consider your audience when writing a play?

Always. My plays are written for their audience. Me and the actors are servants to them. When I write I see the work in performance – in space, in time, with people actively watching and listening and contributing their imagination. I leave space in my plays to allow the audience in. In my plays I often characterise them – members of a cult, an audience of another show, a grieving widow, recipients of a lecture. In my latest play, Truth’s a Dog Must to Kennel, there are two audiences, an imagined one on top of the real one. The audience is everything.

- Do you have a favourite playwright past or present?

I return repeatedly to Caryl Churchill and try to figure out how her brain works. She packs more density into a line than any writer I know – while also achieving a breathless simplicity.

Also, I can’t seem to leave Shakespeare alone. He’s in everything. I have a series of monologues responding to his minor characters; I’ve directed and acted in a number of his plays. His theatre is closest to my ideal – a theatre of language and imagination.

- What tips would you give to someone who was starting out as a playwright?

Think long and hard about what you want to see on stage. Then work to make it happen. See your words as a stepping stone to a live encounter. Don’t think you’re writing Literature with a capital ‘L’. Don’t feel like you have to finish everything. As an audience, I want to be entrusted with some space for me to exist in. Tell a story. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by possibility, just tell a story from beginning to end and then work out HOW to tell it. Or rather, how that story needs to be told.

- How much research do you do before you start writing a play?

Research is oblique to the creative process. I run a mile from dramatised research. Use it to trigger your responses but then go free. In theatre, one is never really writing about the thing you say you are writing about. There’s always another level. Too much research will suffocate that other level and we get into the territory of journalism. Journalism does journalism really well, so leave it alone – unless you want to be a journalist.

- What advice would you give to your teenage self?

Don’t panic. Things will happen eventually if you remain open to them. Stay open. Live your life. Stay open. Follow your interests. Stay open. See stuff. Stay open. Eventually, your work will come out into the open.

Join Tim Crouch at October’s First Tuesday Writers Club to explore writing through performance through a mix of practical exercises and thinking around ideas of performance and the written word.

Emotional Truth — with Yvvette Edwards

First Tuesday Writers | 7th April 2026 Online | Price: £25